Table of Contents

How Messes Breed Good Ideas

Early last year I read Where Good Ideas Come From. I tend to prefer fiction books for my non-educational reading outside of work and school, but this one came highly recommended and I found myself agreeing with a lot of the takeaways. One of the key concepts of the book that I've been mulling over in my head is the importance of messes.

Messes help to facilitate the cross-pollination of ideas. That doesn't mean organization is negative. But if objects and ideas become too organized, then arbitrary divisions between topics can start to form. This in turns can hinder creativity and lateral thinking. When objects and ideas aren't stored in an organized manner, you start to conflate them and make connections that aren't obvious normally. This is where real innovation is born.

The canonical example of the scientific importance of a good mess comes from the invention of penicillin. The antibiotic was discovered by accident when Alexander Fleming came back to his lab after a vacation. He found a strange mold that had begun to form on one of his staphylococcus petri dishes. That mold turned out to be penicilin and Fleming's carelessness and contaminated lab environment has gone on to save countless millions of lives.

This story follows a common pattern for many of the great inventions and discoveries in history. Every once in a while someone vaults their field forward, not by studying that field at a more granular level, but by thinking laterally and inventing an entirely new branch of ideas. Over the course of human history, specialization of knowledge has become quite deep. Often you have to have a PhD and spend a career studying one topic to discover something new within that field. But frequently, quantum leaps in scientific and technological fields don't come about from pure immersion into that topic. Quite often, ideas that shake industries and human technology come from some foreign catalyst that has nothing to do with the topic at hand. Breakthroughs tend to happen when an immersed mind is allowed to breathe briefly.

This kind of environment can be recreated for anyone with a bit of thoughtfulness and structure. In order to achieve that environment, you just have to organize your thoughts a bit carelessly.

The Allure of Structure

All of this isn't to say that you should leave your computer and go throw things around in your place of living hoping to cure cancer. I don't want to make it seem like I'm giving excuses to live in a pig sty in the small hope of striking intellectual gold.

I'm actually a person who really thrives on structure and order. I find that I'm freer to think about things when I have a blank canvas of physical and mental space. Messes tend to distract me and bring a bit of unnecessary stress to my life. I like things like filesystems for organizing ideas and try to keep a very clean computer and notebook layout. I pride myself on being able to clear my mind until I need to index things. It's for this reason that I've kept a moleskine journal for the past seven years or so.

I find that the exercise of journaling can feel like a mental burden is being alleviated. When I journal I get the feeling that a thought is set in paper, so now it doesn't have to trouble me quite as much -- I can come back to it any time. I find the same calm from organizing the space in which I live so that I can find things easily when I need them, but not have to think about them when I'm not looking at them. In general I tend to naturally incline towards neatness.

But there is one concept that I'm naturally drawn to even more than neatness -- graphs.

Controlling Messes with Graphs

Graphs have a way of imposing order on chaos.

Graphs and networks have been a fascination of mine since I began programming. I read and loved Barabási's Network Science Book, which is freely available online, while I was an undergrad. I can't recommend it enough if you're even moderately interested in the mathematical properties of graphs. I have an on again, off again relationship with Daphne Koller's Probabilistic Graphical Modeling course, which helps answer the question "if correlation doesn't equal causation, then what the hell does?". And I'm even using a particle background on this site. In general, I'm drawn to them like a moth to a flame. There's just something satisfying about the structure of a graph and the mathematical truths that they contain. They feel like a tool that can solve most problems that a social species like humanity might run up against.

And as someone who enjoys a good graph, imagine my luck when I found out that graphical notetaking has been rising in popularity with tech employees for the past few years. Even before I read Where Good Ideas Come From, I was independently looking into graphical notetaking. I am an avid physical notetaker and I enjoy the therapeutic benefits of journaling or the memory-forming properties of writing by hand, but at the end of the day, it's much faster for me to take down and organize information on a computer.

I had heard of people using Org Mode for Emacs for years. But even before I picked up my VSCode habit I was a consistent Vim user. Additionally, org mode doesn't lend itself to visualization, which I thought was important for being able to visualize patterns in my thoughts.

Eventually a coworker showed me Roam Research. It's a platform that offers graphical notetaking by adding the ability to create links between pages of notes. Once you've linked your notes you can review things in a graphical format by viewing the landscape of your ideas. I read the whitepaper on the ideas behind Roam and signed up for an early version of the app. I didn't realize it at the time, but I was starting to embrace messes. I just didn't know it because in a graph, all the nodes in the mess are linked.

Unfortunately, when I attempted to show Roam to a friend a couple months after picking it up, I noticed that they had begun to charge a subscription fee for the app. I sought out a free version and fell in love with Foam. The main reasons I made the switch were:

- Foam is open-source

- Foam is free

- Foam notes are git-tracked

- Foam notes live in my filesystem

- VSCode editing (text manipulation and color themes)

And so far I've been absolutely loving Foam. It's been a staple in my daily notes for everything from work ticket tracking to personal project management to general scratch for random ideas and essays.

Implicit vs. Explicit Structure

One thing that drew me to Foam over Roam was the idea that I could keep my notes in my filesystem. This meant both that I could control the security of my notes and also that I could organize them as I pleased in directories. As a filesystem neat-freak, this appealed to me since I could maintain the graph shape, while still categorizing and filing notes for my own indexing. I could easily find notes on any topic and still see how they linked to each other visually.

As I adopted this filesystem approach with my notes, though, I started to notice the shape of the graph changing.

My notes weren't taking the shape of a graph, they were just a filesystem! When I split my notes up between directories I noticed that they began to constellate and create shapes. At first, I was enamored with the constellations forming out of my notes. I figured these must be my thought patterns visualized. What I didn't realize was that these constellations meant I was losing all of the benefits of a graphical notetaking system. I was imposing explicit structure on the notes that I was taking down, and thereefore the ideas in my head.

It was right around the time that I switched to Foam that I started reading Where Good Ideas Come From. When I reflected a bit on the environments of great innovators, I noticed the errors in my notes system. Understanding the importance of cross-pollinating ideas gave me a new perspective on the purpose of my notes. They shouldn't be a series of unrelated ideas that only connect within their respective category, that's too neat. Ideas should be messy. The structure of your notes should exist implicitly in the connections between thoughts, rather than within arbitrary divisions of topics. That is the point of being able to link between any pair of notes.

I did the only thing that I could think of to impose a mess on my beautiful over-organized notes. I dumped all the hundreds of .md files into one monolith directory. The arbitrary category delineations would still be there, but as I took more notes, the walls between ideas began to break down. My thoughts were forced to cross-pollinate. Reviews of books I had read were adjacent to work ticket notes, which were adjacent to silly descriptions of fun nights out. The structure (or lack thereof) started to give me more license to connect notes that would not normally be linked. My notes became more fun to wander through. Instead of parsing through them like a binary tree, I could amble around and see how my thoughts connected. And, of course, VSCode still allowed me to search for any given note easily.

Neuroscience and Graphs

As I began to think on this implicit structure and organization of my notes, I started making more and more connections to the human brain. I reflected on the general allure of a good notetaking system. Why have I and others like myself been drawn to the concept of more faithfully representing our brains on paper?

I think there's a certain calm that comes from knowing that ideas have been taken down. It's like writing to disk when we've been storing too much information in RAM. A notetaking system allows us to create a new brain that's on paper, freeing up resources to do things humans are better at, like making connections and seeing patterns. We create an external brain that we can query whenever we want to hone in on a specific pattern of thoughts, rather than have the ideas float around in our brain. The brain wants to represent itself.

And of course, there are a ton of people who have already made the connection between notes and how they map the human brain. The concept of a second brain that exists on paper is closely linked with the idea of Zettelkasten. Originally invented as a primitive link-based note-taking system, it's since become a common tool for people of all disciplines to organize their thoughts. Roam and Foam are both Zettelkasten systems since they allow notes to link between each other.

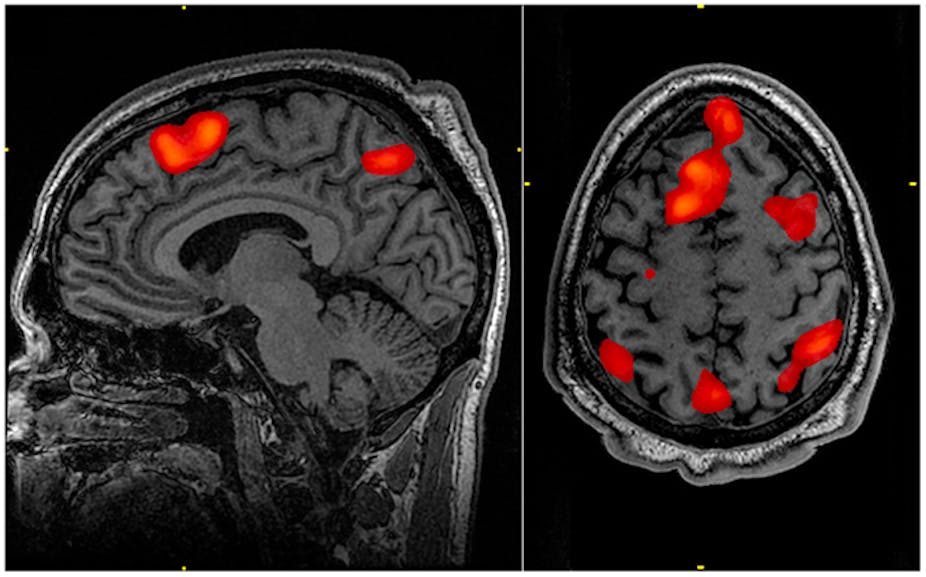

What I started to realize as I shifted my notes more towards a messy single-directory approach, was that I had accidentally structured them more similarly to the human brain. My education is in Biomedical Engineering so I tend to fall back to the human body for modeling a lot of phenomena. Hearing some of the concepts of the second brain brought me back to some days in the lab. I started to make connections between the jumbled mass of notes that I was creating and a technique called functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI.

The main idea of fMRI is the mapping of brain function based on where blood is flowing in the brain at a given time. This method has allowed neuroscientists to map all sorts of human thought patterns to areas within the brain. This structural/locational linking has led to more targeted treatment of cognitive conditions. But what's interesting about fMRI is that it allows analysis of the implicit structure of the brain rather than the explicit physical structure. The brain's functional structure is defined only by the connections between various areas and has only a vague relation to the physical layout. We can say general things like "Wernicke's area controls speech and that's roughly here", but with fMRI, we can analyze the connections being made in the brain to know exactly which areas are being engaged during a series of thoughts.

The brain is essentially a big unorganized mess of neurons from which order emerges when you track the flow of ideas. When you track how things are moving around and mixing within that mess, then it becomes a graph.

Integrating Physical and Digital Notes

So at after figuring all this out there was only one piece left out in my notetaking puzzle: where would my old faithful moleskine fit in? Why would I need to use a physical, paper notebook to track anything when I had this sophistocated piece of open-source software doing it for me? I thought on ways to fit the two mediums together without repeating information and eventually came to my current setup.

I would allow my digital notes to be a mess. Then my physical notebook would be for journaling, and drawing conclusions from the mess of my notes. I decided that I would let the notes being churned out and connected within Foam become my amorphous unconscious, while my physical notebook would be my interpreter for recognizing patterns within the notes.

Foam allows you to view connections to and from a given note quite easily. Using this feature, I usually take a few minutes at the end of the day to traverse where my thoughts have been wandering and patterns start to form throughout the day. For a given ticket at work, this is like the detective tracing the lines of yarn across the room and discovering who was the criminal mastermind all along. But in my case it's a little less interesting and usually comes down to an improper assumption somewhere in our codebase.

I feel that this process of allowing the chaos of your mind to be dumped into the real world and then interpreted by your own conscious mind is extremely valuable. I find myself thinking in higher order ways and viewing situations from new perspectives. But in the end, I know this won't be my final note-taking system forever. Maybe the only thing that my notes have taught me over the years is that I'm always changing. If our brains want to represent themselves and they're always constantly changing, then I fear I may be doomed to constantly changing the way I take notes. Hopefully I'll be there with my moleskine to write down when it happens.

All the best, Mickey